Jingshan Park is a vast island of green at the heart of China’s capital – a network of paths that weave in and out of secluded groves, twisted rock sculptures, and water features.

Perhaps best known for its hilltop pagoda and the stunning view it affords of the Forbidden City’s impressive rear, Jingshan was intended only as a place we had to pass through on our way to Beijing’s most famous landmark.

At first it felt like every other Chinese park my travels had taken me through. The twisted willows and the regal poplar were beautiful, but nothing I hadn’t seen on the shores of Hangshou’s West Lake or Nanjing’s Xuanwu Lake.

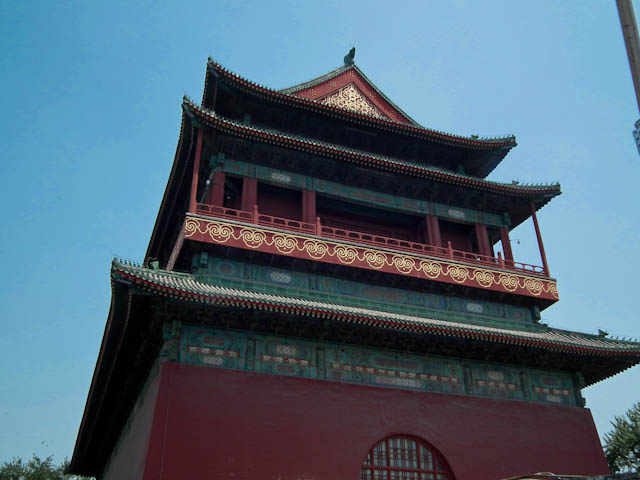

“I would kill to lie in that grass,” I inform Corinne as we make our way into the park. It’s been another criminally hot day in Beijing, and our morning has been spent climbing up and down the stairs in the Bell & Drum Towers.

I’m onto my fourth or fifth bottle of water for the day, and the idea of stretching out on deliciously green grass is right up there with getting to third base with Scarlett Johannsen on my wish list right about now.

My mind is already on post Forbidden City Beijing duck and beers and I’m perhaps guilty of not immediately appreciating how picturesque Jingshan is. For all of their aptitude at building vast concrete jungles in record time, the Chinese are also masters of creating beautiful parklands at the heart of even the most rapidly developing industrial city.

A Chinese park is far more than simply a place to throw around a football or have a picnic lunch. Centuries of tradition have made the creation of parks an art form. That’s not hyperbole either. Chinese parks are works of art in their own right. The pagodas, the ponds, the gardens, the trees, and even the hills are woven together in a living tapestry that expresses some aspect of Chinese culture that we as visitors are perhaps only able to appreciate on a surface level.

Perhaps my past experiences in other parks have dulled my senses somewhat.

“This is nice,” I observe aloud, but my appreciation doesn’t immediately go beyond that.

It’s as we’ve rounded a corner and are walking ‘neath the shade that exists between a line of trees and a high, rocky outcrop that we hear the first strains of singing.

We find the singers – a group of elderly Chinese gentlemen clustered around a bench upon which an accordion player sites – and are momentarily struck dumb. The seven or eight men sing operatically in perfect harmony, passing around a single sheet of lyrics to any newcomer who wishes to join.

As if their music opens our ears further to the noises of the park, we’re soon drawn to an even louder choir. At the foot of the hill leading up to the park’s famed pagoda, we come across a horde of locals. Men and women alike stand in a messy circle around a single conductor and together they belt out tunes from a different time.

The men and women harmonise at times and at other times sing separate refrains. The spectacle is utterly enchanting. It’s all I can do to fumble my phone out of my pocket and try to capture the moment as best I can, and I know Corinne is similarly astounded by the display.

The sheer beauty of their singing is enough to move both of us to the verge of tears. The strength of community that must exist to draw these people together in their shared love of the songs they sing and the country they sing for is something alien to somebody from emotionally distant Australia.

It’s how I imagine church must feel to those who don’t yawn their way through sermons.

It was during that entirely unexpected serenity that a second thought dawn upon me and conjured up a different kind of tears.

Listening to these elderly people sing the songs of a time before China opened its doors to the western world, I was reminded of a very sobering fact:

This very beautiful display dies with them.

The children of modern China are more concerned with Game of Thrones, DoTA, and the Kobe versus LeBron debate to have even learned these proud songs of Chinese imperialism. The only songs I ever heard my students singing were from whatever K-Pop idol had made the biggest splash of late.

My children, should I ever accidentally father some, won’t be able to hear this display. They can visit the same park and marvel at the same view, but there is a very finite amount of time left to see and hear the last generation from ‘old China’.

The world is getting smaller by the day, and these vestiges of a time when countries weren’t all quite as eager to be the same as one another are getting fewer and farther between.

The Great Wall of China, barring some disaster, will remain for generations of tourists to see.

But there’s a very small window of time left to experience Jingshan Park and hear the singing on a Sunday afternoon.

Knowing this, and realising just how lucky I am to have witnessed it, the tears came anew.

Jingshan Park, a place I hadn’t even thought of as a ‘must see’ when planning my Beijing trip, turned out to be one of the most affecting travel experiences I’ve ever had.

Your Say

Have you ever been completely surprised by a place you hadn’t expected much from?